The American Theater was a

theater

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors or actresses, to present the experience of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a stage. The perfor ...

of operations during

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

including all

continental American

''Continental American'' is the third studio album by Peter Allen, released in 1974. The album was his first for A&M Records, and is notable for the inclusion of Allen's version of his co-authored hit for Olivia Newton-John, among others, "I Hon ...

territory, and extending into the ocean.

Owing to North and South America's geographical separation from the central theaters of conflict (in

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

,

the Mediterranean and Middle East, and

the Pacific) the threat of an

invasion of the continental U.S. or other areas in the Americas by the

Axis Powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

was negligible and the theater saw relatively little conflict.

However, despite the relative unimportance of the American Theater, some battles took place within it, including the

Battle of the River Plate

The Battle of the River Plate was fought in the South Atlantic on 13 December 1939 as the first naval battle of the Second World War. The Kriegsmarine heavy cruiser , commanded by Captain Hans Langsdorff, engaged a Royal Navy squadron, command ...

,

submarine attacks off the East Coast, the

Aleutian Islands campaign, the

Battle of the St. Lawrence

The Battle of the St. Lawrence involved marine and anti-submarine actions throughout the lower St. Lawrence River and the entire Gulf of Saint Lawrence, Strait of Belle Isle, Anticosti Island and Cabot Strait from May–October 1942, September ...

, and the attacks on

Newfoundland. Espionage efforts included

Operation Bolívar

Operation Bolívar was the codename for the German espionage in Latin America during World War II. It was under the operational control of Department VID 4 of Germany's Security Service, and was primarily concerned with the collection and trans ...

.

German operations

South America

''See also

Latin America during World War II

During World War II, a number of significant economic, political, and military changes took place in Latin America. The war caused considerable panic in the region over economics as large portions of economy of the region depended on the European ...

''

Battle of the River Plate

The first naval battle during the war was fought on December 13, 1939, off the Atlantic coast of

South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the southe ...

. The German "

pocket battleship

The ''Deutschland'' class was a series of three ''Panzerschiffe'' (armored ships), a form of heavily armed cruiser, built by the ''Reichsmarine'' officially in accordance with restrictions imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. The ships of the cl ...

" (acting as a commerce raider) encountered one of the British naval units searching for her. Composed of three

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

cruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. Modern cruisers are generally the largest ships in a fleet after aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships, and can usually perform several roles.

The term "cruiser", which has been in use for several hu ...

s, , , and , the unit was patrolling off the

River Plate estuary of

Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

and

Uruguay

Uruguay (; ), officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay ( es, República Oriental del Uruguay), is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast; while bordering ...

. In a bloody engagement, ''Admiral Graf Spee'' successfully repulsed the British attacks.

Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

Hans Langsdorff

Hans Wilhelm Langsdorff (20 March 1894 – 20 December 1939) was a German naval officer, most famous for his command of the German pocket battleship ''Admiral Graf Spee'' during the Battle of the River Plate off the coast of Uruguay in 1939. ...

then brought his damaged ship to shelter in neutral Uruguay for repairs. However, British intelligence successfully deceived Langsdorff into believing that a much superior British force had now gathered to wait for him, and he

scuttled

Scuttling is the deliberate sinking of a ship. Scuttling may be performed to dispose of an abandoned, old, or captured vessel; to prevent the vessel from becoming a navigation hazard; as an act of self-destruction to prevent the ship from being ...

his ship at

Montevideo

Montevideo () is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Uruguay, largest city of Uruguay. According to the 2011 census, the city proper has a population of 1,319,108 (about one-third of the country's total population) in an area of . M ...

to save his crew's lives before committing suicide. German combat losses were 96 killed or wounded, against 72 British sailors killed and 28 wounded. Two Royal Navy cruisers had been severely damaged.

Submarine warfare

U-boat operations in the region (centered in the

Atlantic Narrows

The Atlantic Narrows is a relatively narrow portion of the Atlantic Ocean between South America and West Africa. More specifically, it lies approximately at the Equator where by definition the North Atlantic meets the South Atlantic and roughl ...

between

Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

and

West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Maurit ...

) began in autumn 1940. After negotiations with Brazilian Foreign Minister

Osvaldo Aranha

Oswaldo Euclides de Sousa Aranha (, 15 February 1894 – 27 January 1960) was a Brazilian politician, diplomat and statesman, who came to national prominence in 1930 under Getúlio Vargas.

Considered a moderate by many in and outside of Brazil, ...

(on behalf of dictator

Getúlio Vargas

Getúlio Dornelles Vargas (; 19 April 1882 – 24 August 1954) was a Brazilian lawyer and politician who served as the 14th and 17th president of Brazil, from 1930 to 1945 and from 1951 to 1954. Due to his long and controversial tenure as Brazi ...

), the

U.S.

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

introduced its

Air Force

An air force – in the broadest sense – is the national military branch that primarily conducts aerial warfare. More specifically, it is the branch of a nation's armed services that is responsible for aerial warfare as distinct from an a ...

along Brazil's coast in the second half of 1941. Germany and Italy subsequently extended their submarine attacks to include Brazilian ships wherever they were, and from April 1942 were found in Brazilian waters. On 22 May 1942, the first Brazilian attack (although unsuccessful) was carried out by

Brazilian Air Force

"Wings that protect the country"

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march = Hino dos Aviadores

, mascot =

, anniversaries = 22 May (anniver ...

aircraft on the . After a series of attacks on merchant vessels off the Brazilian coast by , Brazil officially entered the war on 22 August 1942, offering an important addition to the Allied strategic position in the South Atlantic. Although the

Brazilian Navy

)

, colors= Blue and white

, colors_label= Colors

, march= "Cisne Branco" ( en, "White Swan") (same name as training ship ''Cisne Branco''

, mascot=

, equipment= 1 multipurpose aircraft carrier7 submarines6 frigates2 corvettes4 amphibious warf ...

was small, it had modern minelayers suitable for coastal convoy escort and aircraft which needed only small modifications to become suitable for

maritime patrol {{Unreferenced, date=March 2008

Maritime patrol is the task of monitoring areas of water. Generally conducted by military and law enforcement agencies, maritime patrol is usually aimed at identifying human activities.

Maritime patrol refers to ac ...

. During its three years of war, mainly in Caribbean and South Atlantic, alone and in conjunction with the U.S., Brazil escorted 3,167 ships in 614 convoys, totalling 16,500,000 tons, with losses of 0.1%. Brazil saw three of its warships sunk and 486 men

killed in action (332 in the cruiser

''Bahia''); 972

seamen and civilian passengers were also lost aboard the 32 Brazilian merchant vessels attacked by enemy submarines. American and Brazilian air and naval forces worked closely together until the end of the Battle. One example was the sinking of in July 1943, by a coordinated action of Brazilian and American aircraft.

Only in Brazilian waters, eleven other Axis submarines were known sunk between January and September 1943—the Italian and ten German boats: , , , , , , , , , and .

[

By late 1943, the decreasing number of Allied shipping losses in South Atlantic coincided with the increasing elimination of Axis submarines operating there. From then, the battle in the region was lost for Germans, even with the most of remaining submarines in the region receiving official order of withdrawal only in August of the following year, and with (''Baron Jedburgh'') the last Allied merchant ship sunk by a U-boat (''U-532'') there, on 10 March 1945.

]

United States

Duquesne Spy Ring

Even before the war, a large Nazi spy ring was found operating in the United States. The Duquesne Spy Ring is still the largest espionage case in United States history that ended in convictions. The 33 German agents who formed the Duquesne spy ring were placed in key jobs in the United States to get information that could be used in the event of war and to carry out acts of sabotage. One man opened a restaurant and used his position to get information from his customers; another worked at an airline so he could report Allied ships crossing the

Even before the war, a large Nazi spy ring was found operating in the United States. The Duquesne Spy Ring is still the largest espionage case in United States history that ended in convictions. The 33 German agents who formed the Duquesne spy ring were placed in key jobs in the United States to get information that could be used in the event of war and to carry out acts of sabotage. One man opened a restaurant and used his position to get information from his customers; another worked at an airline so he could report Allied ships crossing the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

; others in the ring worked as deliverymen so they could deliver secret messages alongside normal messages. The ring was led by Captain Fritz Joubert Duquesne

Frederick "Fritz" Joubert Duquesne (; 21 September 187724 May 1956; sometimes Du Quesne) was a South African Boer and German soldier, big-game hunter, journalist, and spy. Many of the claims Duquesne made about himself are in dispute; over his l ...

, a South African Boer

Boers ( ; af, Boere ()) are the descendants of the Dutch-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape Colony, Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controll ...

who spied for Germany in both World Wars and is best known as "The man who killed Kitchener" after he was awarded the Iron Cross

The Iron Cross (german: link=no, Eisernes Kreuz, , abbreviated EK) was a military decoration in the Kingdom of Prussia, and later in the German Empire (1871–1918) and Nazi Germany (1933–1945). King Frederick William III of Prussia est ...

for his key role in the sabotage and sinking of in 1916.double agent

In the field of counterintelligence, a double agent is an employee of a secret intelligence service for one country, whose primary purpose is to spy on a target organization of another country, but who is now spying on their own country's organi ...

for the United States, was a major factor in the FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and its principal Federal law enforcement in the United States, federal law enforcement age ...

's successful resolution of this case. For nearly two years, Sebold ran a secret radio station in New York for the ring. Sebold provided the FBI with information on what Germany was sending to its spies in the United States while allowing the FBI to control the information that was being transmitted to Germany. On June 29, 1941, six months before the U.S. declared war, the FBI acted. All 33 spies were arrested, found or pled guilty, and sentenced to serve a total of over 300 years in prison.

Operation Pastorius

After declaring war on the United States following the attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii, j ...

, Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

ordered the remaining German saboteur

Sabotage is a deliberate action aimed at weakening a polity, effort, or organization through subversion, obstruction, disruption, or destruction. One who engages in sabotage is a ''saboteur''. Saboteurs typically try to conceal their identiti ...

s to wreak havoc on America. The responsibility for carrying this out was given to German Intelligence ( Abwehr). In the spring of 1942, nine agents were recruited (one eventually dropping out) and divided into two teams. The first, commanded by George John Dasch, included Ernst Peter Burger

Ernst Peter Burger (September 1, 1906 – October 9, 1975) was a German-American who was a spy and saboteur for Germany during World War II. He was captured but escaped execution. He was deported to Germany in 1948.

Operation Pastorius

Born in ...

, Heinrich Heinck, and Richard Quirin; the second, under command of Edward Kerling, included Hermann Neubauer, Werner Thiel, and Herbert Haupt.

On June 12, 1942, the landed Dasch's team with explosives and plans at Amagansett, New York

Amagansett is a census-designated place that roughly corresponds to the hamlet by the same name in the Town of East Hampton in Suffolk County, New York, United States, on the South Shore of Long Island. As of the 2010 United States Census, ...

. Their mission was to destroy power plants at Niagara Falls and three Aluminum Company of America (ALCOA

Alcoa Corporation (an acronym for Aluminum Company of America) is a Pittsburgh-based industrial corporation. It is the world's eighth-largest producer of aluminum. Alcoa conducts operations in 10 countries. Alcoa is a major producer of primary ...

) factories in Illinois, Tennessee, and New York. However, Dasch instead turned himself in to the FBI, providing them with a complete list of his team members and an account of the planned missions, which led to their arrests.

On June 17, Kerling's team landed from '' U-584'' at Ponte Vedra Beach

Ponte Vedra Beach is a wealthy unincorporated seaside community and suburb of Jacksonville, Florida in St. Johns County, Florida, United States. Located southeast of downtown Jacksonville and north of St. Augustine, it is part of the Jackso ...

, south-east of Jacksonville, Florida

Jacksonville is a city located on the Atlantic coast of northeast Florida, the most populous city proper in the state and is the largest city by area in the contiguous United States as of 2020. It is the seat of Duval County, with which the ...

. They were ordered to place mines in four areas: the Pennsylvania Railroad

The Pennsylvania Railroad (reporting mark PRR), legal name The Pennsylvania Railroad Company also known as the "Pennsy", was an American Class I railroad that was established in 1846 and headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was named ...

in Newark, New Jersey

Newark ( , ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of New Jersey and the seat of Essex County and the second largest city within the New York metropolitan area.[St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi River, Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the Greater St. Louis, ...]

, and Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

; and New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

's water supply pipes. The team members made their way to Cincinnati and then split up, two going to Chicago, Illinois

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

, and the others to New York. Dasch's confession led to the arrest of all of the men by July 10.

Because the German agents were captured in civilian clothes (though they had landed in uniforms), they were tried by a military tribunal

Military justice (also military law) is the legal system (bodies of law and procedure) that governs the conduct of the active-duty personnel of the armed forces of a country. In some nation-states, civil law and military law are distinct bodie ...

in Washington D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, Na ...

, with six of them sentenced to death for spying

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information (intelligence) from non-disclosed sources or divulging of the same without the permission of the holder of the information for a tangibl ...

. President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

approved the sentences. The constitutionality of military tribunals was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

in '' Ex parte Quirin'' on July 31, and the six men were executed by electrocution at the D.C. jail

The District of Columbia Jail or the D.C. Central Detention Facility (commonly referred to as the D.C. Jail) is a jail run by the District of Columbia Department of Corrections in Washington, D.C., United States. The Stadium–Armory station s ...

on August 8. Dasch and Burger were given thirty-year prison sentences because they had turned themselves in to the FBI and provided information about the others. Both were released in 1948 and deported to Germany. Dasch (aka George Davis), who had been a longtime American resident before the war, suffered a difficult life in Germany after his return from U.S. custody because he had betrayed his comrades to the U.S. authorities. As a condition of his deportation, he was not permitted to return to the United States, even though he spent many years writing letters to prominent American authorities (J. Edgar Hoover, President Eisenhower, etc.) seeking permission to return. He eventually moved to Switzerland and wrote a book, titled ''Eight Spies Against America''.

Operation Magpie

In 1944 another attempt at infiltration was made, codenamed Operation Elster ("Magpie"). Elster involved Erich Gimpel Erich Gimpel (25 March 1910 in Merseburg – 3 September 2010 in São Paulo) was a German spy during World War II. Together with William Colepaugh, he took part in Operation Elster ("Magpie") an espionage mission to the United States in 1944, but ...

and German-American defector William Colepaugh

William Curtis Colepaugh (March 25, 1918 – March 16, 2005) was an American who, following his 1943 discharge from the U.S. Naval Reserve ("for the good of the service", according to official reports), defected to Nazi Germany in 1944. While a cre ...

. Their mission's objective was to gather intelligence on a variety of military subjects and transmit it back to Germany by a radio to be constructed by Gimpel. They sailed from Kiel on and landed at Hancock Point, Maine, on November 29, 1944. Both then made their way to New York, but the operation soon collapsed. Colepaugh lost his nerve and turned himself in to the FBI on December 26, confessing the whole plan and naming Gimpel. Gimpel was then arrested four days later in New York. Both men were sentenced to death, but eventually their sentences were commuted. Gimpel spent 10 years in prison, while Colepaugh was released in 1960 and operated a business in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania

King of Prussia (also referred to as KOP) is a census-designated place in Upper Merion Township in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, United States. As of the 2020 census, its population was 22,028. The community took its unusual name in the 18th ...

, before he retired to Florida.

Nazi landings in Canada

St. Martins, New Brunswick

One month earlier than the Dasch operation (on May 14, 1942), a solitary Abwehr agent, Marius A. Langbein, was landed by a U-boat () near St. Martins, New Brunswick, Canada. His mission, codenamed Operation Grete, after the name of the agent's wife, was to observe and report shipping movements at Montreal and Halifax, Nova Scotia (the main departure port for North Atlantic convoys). Langbein, who had lived in Canada before the war, changed his mind and moved to Ottawa, where he lived off his Abwehr funds until he surrendered to the Canadian authorities in December 1944. A jury found Langbein not guilty of spying, since he had never committed any hostile acts against Canada during the war.

New Carlisle, Quebec

In November 1942, sank two iron ore freighters and damaged another off Bell Island in Conception Bay, Newfoundland, en route to the

In November 1942, sank two iron ore freighters and damaged another off Bell Island in Conception Bay, Newfoundland, en route to the Gaspé Peninsula

The Gaspé Peninsula, also known as Gaspesia (; ), is a peninsula along the south shore of the Saint Lawrence River that extends from the Matapedia Valley in Quebec, Canada, into the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. It is separated from New Brunswick o ...

where, despite an attack by a Royal Canadian Air Force

The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF; french: Aviation royale canadienne, ARC) is the air and space force of Canada. Its role is to "provide the Canadian Forces with relevant, responsive and effective airpower". The RCAF is one of three environm ...

aircraft, it successfully landed a spy, Werner von Janowski

Werner Alfred Waldemar von Janowski, (Abwehr-codenamed "Bobbi"; Allied-codenamed WATCHDOG), was a captured German Second World War Nazi spy and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police's first double agent. He is believed to have been a triple agent by ...

, four miles (6.5 km) from New Carlisle, Quebec

New Carlisle, Quebec is a town in the Gaspésie–Îles-de-la-Madeleine region of Quebec, Canada. It best known as the boyhood home of René Lévesque although he was born in Campbellton, New Brunswick. Its population is approximately 1,388, most ...

, at around 5am on November 9, 1942.

Von Janowski showed up at the New Carlisle Hotel at 06:30 and checked in under the alias of William Brenton. The son of the hotel owner, Earle Annett Jr., grew suspicious of him, because of inconsistencies with the German spy's story. He used an out-of-circulation Canadian note when paying his bill to the owner's son and when he left to wait at the train station the suspicious son of the hotelier followed him.

There Annett grew more suspicious and he alerted a Quebec Provincial Police

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

constable, Alfonse Duchesneau, who quickly boarded the train as it pulled away from the station and began searching for the stranger. Duchesneau located von Janowski, who said he was a radio salesman from Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the ancho ...

. He stuck with this story until the policeman asked to search his bags; the stranger then confessed: "That will not be necessary. I am a German officer who serves his country as you do yourself."RCMP

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP; french: Gendarmerie royale du Canada; french: GRC, label=none), commonly known in English as the Mounties (and colloquially in French as ) is the federal and national police service of Canada. As poli ...

and MI5

The Security Service, also known as MI5 ( Military Intelligence, Section 5), is the United Kingdom's domestic counter-intelligence and security agency and is part of its intelligence machinery alongside the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6), G ...

, with spymaster Cyril Mills having been seconded to Canada to assist in the double cross initiative. The effectiveness and honesty of his "turn" is a matter of some dispute. For example, John Cecil Masterman

Sir John Cecil Masterman OBE (12 January 1891 – 6 June 1977) was a noted academic, sportsman and author. His highest-profile role was as Vice-Chancellor of the University of Oxford, but he was also well known as chairman of the Twenty C ...

wrote in ''The Double Cross System'': "In November, WATCHDOG was landed from a U-boat in Canada together with a wireless set and an extensive questionnaire. This move on the part of the Germans threatened an extension of our activities to other parts of the world, but in fact the case did not develop very satisfactorily... WATCHDOG was closed down in the summer f 1943"

German landings in Newfoundland

Weather Station Kurt, Martin Bay

Accurate weather reporting was important to the sea war and on September 18, 1943, sailed from Kiel

Kiel () is the capital and most populous city in the northern Germany, German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a population of 246,243 (2021).

Kiel lies approximately north of Hamburg. Due to its geographic location in the southeast of the J ...

, via Bergen

Bergen (), historically Bjørgvin, is a city and municipality in Vestland county on the west coast of Norway. , its population is roughly 285,900. Bergen is the second-largest city in Norway. The municipality covers and is on the peninsula of ...

, Norway, with a meteorological team led by Professor Kurt Sommermeyer. They landed at Martin Bay, a remote location near the northern tip of Labrador

, nickname = "The Big Land"

, etymology =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Canada

, subdivision_type1 = Province

, subdivision_name1 ...

on October 22, 1943, and successfully set up an automatic weather station ("Weather Station Kurt

Weather Station Kurt (Wetter-Funkgerät Land-26) was an automatic weather station, erected by a German U-boat crew in northern Labrador, Dominion of Newfoundland, in October 1943. Installing the equipment for the station was the only known armed ...

" or "''Wetter-Funkgerät Land-26''"), despite the constant risk of Allied air patrols.Canadian War Museum

The Canadian War Museum (french: link=no, Musée canadien de la guerre; CWM) is a national museum on the country's military history in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. The museum serves as both an educational facility on Canadian military history, in ad ...

.

U-boat operations

Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean was a major strategic battle zone (the "Battle of the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic, the longest continuous military campaign in World War II, ran from 1939 to the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, covering a major part of the naval history of World War II. At its core was the Allied naval blockade ...

") and when Germany declared war on the U.S., the East Coast of the United States

The East Coast of the United States, also known as the Eastern Seaboard, the Atlantic Coast, and the Atlantic Seaboard, is the coastline along which the Eastern United States meets the North Atlantic Ocean. The eastern seaboard contains the coa ...

offered easy pickings for German U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare role ...

s (referred to as the " Second Happy Time"). After a highly successful foray by five Type IX

The Type IX U-boat was designed by Nazi Germany's '' Kriegsmarine'' in 1935 and 1936 as a large ocean-going submarine for sustained operations far from the home support facilities. Type IX boats were briefly used for patrols off the eastern Un ...

long-range U-boats, the offensive was maximized by the use of short-range Type VII U-boats, with increased fuel stores, replenished from supply U-boats called ''Milchkühe'' (milk cows). From February to May 1942, 348 ships were sunk, for the loss of two U-boats during April and May. U.S. naval commanders were reluctant to introduce the convoy system that had protected trans-Atlantic shipping and, without coastal blackouts, shipping was silhouetted against the bright lights of American towns and cities such as Atlantic City

Atlantic City, often known by its initials A.C., is a coastal resort city in Atlantic County, New Jersey, United States. The city is known for its casinos, Boardwalk (entertainment district), boardwalk, and beaches. In 2020 United States censu ...

until a dim-out was ordered in May.

The cumulative effect of this campaign was severe; a quarter of all wartime sinkings – 3.1 million tons. There were several reasons for this. The American naval commander, Admiral Ernest King

Ernest Joseph King (23 November 1878 – 25 June 1956) was an American naval officer who served as Commander in Chief, United States Fleet (COMINCH) and Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) during World War II. As COMINCH-CNO, he directed the U ...

, as an apparent anglophobe

Anti-English sentiment or Anglophobia (from Latin ''Anglus'' "English" and Greek φόβος, ''phobos'', "fear") means opposition to, dislike of, fear of, hatred of, or the oppression and persecution of England and/or English people.''Oxford ...

, was averse to taking British recommendations to introduce convoys, U.S. Coast Guard and Navy patrols were predictable and could be avoided by U-boats, inter-service co-operation was poor, and the U.S. Navy did not possess enough suitable escort vessels (British and Canadian warships were transferred to the U.S. east coast).

U.S. East Coast

Several ships were torpedoed within sight of East Coast

East Coast may refer to:

Entertainment

* East Coast hip hop, a subgenre of hip hop

* East Coast (ASAP Ferg song), "East Coast" (ASAP Ferg song), 2017

* East Coast (Saves the Day song), "East Coast" (Saves the Day song), 2004

* East Coast FM, a ra ...

cities such as New York and Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

. The only documented World War II sinking of a U-boat close to New England shores occurred on May 5, 1945, when the torpedoed and sank the collier off Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is an American seaside city on Aquidneck Island in Newport County, Rhode Island. It is located in Narragansett Bay, approximately southeast of Providence, Rhode Island, Providence, south of Fall River, Massachusetts, south of Boston, ...

. When ''Black Point'' was hit, the U.S. Navy immediately chased down the sub and began dropping depth charge

A depth charge is an anti-submarine warfare (ASW) weapon. It is intended to destroy a submarine by being dropped into the water nearby and detonating, subjecting the target to a powerful and destructive Shock factor, hydraulic shock. Most depth ...

s. In recent years, ''U-853'' has become a popular dive site. Its intact hull, with open hatches, is located in of water off Block Island

Block Island is an island in the U.S. state of Rhode Island located in Block Island Sound approximately south of the mainland and east of Montauk Point, Long Island, New York, named after Dutch explorer Adriaen Block. It is part of Washingt ...

, Rhode Island. A wreck discovered in 1991 off the New Jersey coast was concluded in 1997 to be that of . Previously, ''U-869'' had been thought to have been sunk off Rabat

Rabat (, also , ; ar, الرِّبَاط, er-Ribât; ber, ⵕⵕⴱⴰⵟ, ṛṛbaṭ) is the capital city of Morocco and the country's seventh largest city with an urban population of approximately 580,000 (2014) and a metropolitan populati ...

, Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to ...

.

U.S. Gulf of Mexico

Once convoys and air cover were introduced in the Atlantic, sinking numbers were reduced and the U-boats shifted to attack shipping in the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an oceanic basin, ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of ...

. During 1942 and 1943, more than 20 U-boats operated in the Gulf of Mexico. They attacked tankers transporting oil from ports in Texas and Louisiana, successfully sinking 56 vessels. By the end of 1943, the U-boat attacks diminished as the merchant ships began to travel in armed convoys.Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

by the on May 12, 1942, killing 26 crewmen. There were 14 survivors. Again, when defensive measures were introduced, ship sinkings decreased.

was the only U-boat sunk in the Gulf of Mexico during the war. Once thought to have been sunk by a torpedo dropped from a U.S. Coast Guard Utility Amphibian J4F aircraft on August 1, 1942, ''U-166'' is now believed to have been sunk two days earlier by depth charges from the passenger ship 's naval escort, the U.S. Navy sub-chaser, '' PC-566''. It is thought that the J4F aircraft may have spotted and attacked another German submarine, , which was operating in the area at the same time. ''U-166'' lies in of water within a mile (1,600 m) of her last victim, ''Robert E. Lee''.

Canada

From the start of the war in 1939 until VE Day, several of Canada's Atlantic coast ports became important to the resupply effort for the United Kingdom and later for the Allied land offensive on the Western Front. Halifax and Sydney, Nova Scotia

Sydney is a former city and urban community on the east coast of Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia, Canada within the Cape Breton Regional Municipality. Sydney was founded in 1785 by the British, was incorporated as a city in 1904, and dissolv ...

, became the primary convoy assembly ports, with Halifax being assigned the fast or priority convoys (largely troops and essential material) with the more modern merchant ships, while Sydney was given slow convoys which conveyed bulkier material on older and more vulnerable merchant ships. Both ports were heavily fortified with shore radar emplacements, searchlight batteries, and extensive coastal artillery stations all manned by RCN and Canadian Army regular and reserve personnel. Military intelligence agents enforced strict blackouts throughout the areas and anti-torpedo nets were in place at the harbor entrances, making a direct attack on those facilities unfeasible because it was impossible for Germany to provide air support. Even though no landings of German personnel took place near these ports, there were frequent attacks by U-boats on convoys departing for Europe once these had reached the mouth of the St. Lawrence. Less extensively used, but no less important, was the port of Saint John which also saw matériel funneled through the port, largely after the United States entered the war in December 1941. The port's location within the protected waters of the Bay of Fundy made it a difficult target for attack. The Canadian Pacific Railway

The Canadian Pacific Railway (french: Chemin de fer Canadien Pacifique) , also known simply as CPR or Canadian Pacific and formerly as CP Rail (1968–1996), is a Canadian Class I railway incorporated in 1881. The railway is owned by Canadi ...

mainline from central Canada (which crossed the state of Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and north ...

) could be used to transport in aid of the war effort.

Although not crippling to the Canadian war effort, given the country's rail network to the east coast ports, but possibly more destructive to the morale of the Canadian public, was the Battle of the St. Lawrence

The Battle of the St. Lawrence involved marine and anti-submarine actions throughout the lower St. Lawrence River and the entire Gulf of Saint Lawrence, Strait of Belle Isle, Anticosti Island and Cabot Strait from May–October 1942, September ...

, when U-boats began to venture upriver and attack domestic coastal shipping along Canada's east coast in the St. Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (french: Fleuve Saint-Laurent, ) is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a (roughly) northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connecting ...

and Gulf of St. Lawrence from early 1942 through to the end of the shipping season in late 1944. From a German perspective this area contained most of the military assets in North America that could realistically be targeted for attack, and therefore the St. Lawrence was the only zone that saw consistent warfare—albeit on a limited scale—in North America during World War II. Residents along the Gaspé coast and the St. Lawrence River and Gulf of St. Lawrence were startled at the sight of maritime warfare off their shores, with ships on fire and explosions rattling their communities, while bodies and debris floated ashore. The number of military losses is not known, although loose estimates can be made based on the number of surface units and submarines sunk.

Newfoundland

Five significant attacks on Newfoundland took place in 1942. On 3 March 1942, launched three torpedoes at St. John's; one hit Fort Amherst

Fort Amherst, in Medway, South East England, was constructed in 1756 at the southern end of the Brompton lines of defence to protect the southeastern approaches to Chatham Dockyard and the River Medway against a French invasion. Fort Amherst is ...

and two more hit the cliffs of Signal Hill below Cabot Tower. In autumn German U-boats attacked four iron ore

Iron ores are rocks and minerals from which metallic iron can be economically extracted. The ores are usually rich in iron oxides and vary in color from dark grey, bright yellow, or deep purple to rusty red. The iron is usually found in the fo ...

carriers serving the DOSCO iron mine at Wabana on Bell Island in Newfoundland's Conception Bay. The ships SS ''Saganaga'' and SS ''Lord Strathcona'' were sunk by on 5 September 1942, while SS ''Rose Castle'' and ''P.L.M 27'' were sunk by on 2 November with the loss of 69 lives. After the sinkings the submarine fired a torpedo that missed its target, the 3,000-ton collier ''Anna T'', and struck the DOSCO loading pier and exploded. On 14 October 1942, the Newfoundland Railway

The Newfoundland Railway operated on the island of Newfoundland from 1898 to 1988. With a total track length of , it was the longest narrow-gauge railway system in North America.

Early construction

]

In 1880, a committee of the Newfoundland Leg ...

ferry was torpedoed by and sunk in the Cabot Strait

Cabot Strait

(; french: détroit de Cabot, ) is a strait in eastern Canada approximately 110 kilometres wide between Cape Ray, Newfoundland and Cape North, Cape Breton Island.

It is the widest of the three outlets for the Gulf of Saint L ...

south of Port aux Basques

Channel-Port aux Basques is a town at the extreme southwestern tip of Newfoundland fronting on the western end of the Cabot Strait. A Marine Atlantic ferry terminal is located in the town which is the primary entry point onto the island of Newfou ...

. ''Caribou'' was carrying 45 crew and 206 civilian and military passengers. One hundred thirty-seven lost their lives, many of them Newfoundlanders.

Half a dozen U-boat wrecks lie in waters around Newfoundland and Labrador, destroyed by Canadian patrols.

Caribbean

A German submarine shelled the American Standard Oil

Standard Oil Company, Inc., was an American oil production, transportation, refining, and marketing company that operated from 1870 to 1911. At its height, Standard Oil was the largest petroleum company in the world, and its success made its co-f ...

refinery at the San Nicolas harbour and the "Arend"/"Eagle" Maatschappij (from the Dutch/British Shell Co.) near the Oranjestad harbour situated on the Island of Aruba

Aruba ( , , ), officially the Country of Aruba ( nl, Land Aruba; pap, Pais Aruba) is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands physically located in the mid-south of the Caribbean Sea, about north of the Venezuela peninsula of ...

(a Dutch colony) and some ships that were near the entrance to Lake Maracaibo

Lake Maracaibo (Spanish: Lago de Maracaibo; Anu: Coquivacoa) is a lagoon in northwestern Venezuela, the largest lake in South America and one of the oldest on Earth, formed 36 million years ago in the Andes Mountains. The fault in the northern se ...

on February 16, 1942. Three tankers

Tanker may refer to:

Transportation

* Tanker, a tank crewman (US)

* Tanker (ship), a ship designed to carry bulk liquids

** Chemical tanker, a type of tanker designed to transport chemicals in bulk

** Oil tanker, also known as a petroleum tank ...

, including the Venezuelan ''Monagas'', were sunk. A Venezuelan gunboat, , assisted in rescuing the crews.

A German submarine shelled the island of Mona, some from the main island of Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and Unincorporated ...

, on March 2.

Central America

Before 1941, the Central American nations had various diplomatic ties with Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and the Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent fo ...

. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, they declared war on the Axis nations. The Central American nations joined the Allied side, broke diplomatic relations with the Axis nations, and initiated persecutions of German and Italian immigrants.

During the course of the war, several merchant ships were sunk in the Caribbean by German submarines, for example the Tela, a Honduran cargo ship sunk by a U-504 submarine in 1942. This led the country to carry out constant air patrols over the coasts under fear of the approach of more German submarines or the general fear of an attack by Germany. Other Central American cargo ships sunk by U-boats are the ''Olancho,'' the ''Comayagua'', and the ''Bluefields'', of Honduran and Nicaraguan origins. Central American volunteers in the United States Army participated in both the European and Asia Pacific theater.

Japanese operations

Aleutian Islands Campaign

Before

Before Operation MI

The Battle of Midway was a major naval battle in the Pacific Theater of World War II that took place on 4–7 June 1942, six months after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor and one month after the Battle of the Coral Sea. The U.S. Navy under Ad ...

could be carried out, the Japanese decided to take the Aleutian Islands. On June 3–4, 1942, Japanese planes from two light carriers and struck the U.S. against the city of Unalaska, Alaska

Unalaska ( ale, Iluulux̂; russian: Уналашка) is the chief center of population in the Aleutian Islands. The city is in the Aleutians West Census Area, a regional component of the Unorganized Borough in the U.S. state of Alaska. Unalask ...

, at Dutch Harbor

Dutch Harbor is a harbor on Amaknak Island in Unalaska, Alaska. It was the location of the Battle of Dutch Harbor in June 1942, and was one of the few sites in the United States to be subjected to aerial bombardment by a foreign power during ...

in the Aleutian Islands

The Aleutian Islands (; ; ale, Unangam Tanangin,”Land of the Aleuts", possibly from Chukchi language, Chukchi ''aliat'', "island"), also called the Aleut Islands or Aleutic Islands and known before 1867 as the Catherine Archipelago, are a cha ...

. Originally, the Japanese planned to attack Dutch Harbor simultaneously with its attack on Midway, but the Midway attack was delayed by one day. The attack only did moderate damage on Dutch Harbor, but 43 Americans were killed and 50 others wounded in the attack.

On June 6, two days after the bombing of Dutch Harbor, 500 Japanese marines landed on Kiska

Kiska ( ale, Qisxa, russian: Кыска) is one of the Rat Islands, a group of the Aleutian Islands of Alaska. It is about long and varies in width from . It is part of Aleutian Islands Wilderness and as such, special permission is required ...

, one of the Aleutian Islands of Alaska. Upon landing, they killed two and captured eight United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

officers

An officer is a person who has a position of authority in a hierarchical organization. The term derives from Old French ''oficier'' "officer, official" (early 14c., Modern French ''officier''), from Medieval Latin ''officiarius'' "an officer," f ...

, then seized control of American soil for the first time. The next day, a total of 1,140 Japanese infantrymen landed on Attu via Holtz Bay Holtz Bay is an inlet on the northeast coast of the island of Attu in the Aleutian Islands in Alaska.

Holtz Bay was among the landing sites of United States Army troops in the Battle of Attu on 11 May 1943, which led to the recapture of the island ...

, eventually reaching Massacre Bay and Chichagof Harbor

Chichagof Harbor is an inlet on the northeast coast of the island of Attu in the Aleutian Islands in Alaska.''Merriam-Webster's Geographical Dictionary, Third Edition'', p. 243. It is named after Russian Admiral and polar explorer Vasily Chichagov ...

. Attu's population at the time consisted of 45 Alaska Native Aleut

The Aleuts ( ; russian: Алеуты, Aleuty) are the indigenous people of the Aleutian Islands, which are located between the North Pacific Ocean and the Bering Sea. Both the Aleut people and the islands are politically divided between the U ...

s, and two white Americans – Charles Foster Jones, a 60-year-old ham radio

Amateur radio, also known as ham radio, is the use of the radio frequency spectrum for purposes of non-commercial exchange of messages, wireless experimentation, self-training, private recreation, radiosport, contesting, and emergency communic ...

operator and weather observer, and his 62-year-old wife Etta, a teacher and nurse. The Japanese killed Charles Jones after interrogating him, while Etta Jones and the Aleut population were sent to Japan, where 16 of the Aleuts died and Etta survived the war.

A year after Japan's occupation of Kiska and Attu, U.S. troops invaded Attu on May 11, 1943 and successfully retook the island after three weeks of fighting, killing 2,351 Japanese combatants and taking only 28 as prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held Captivity, captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold priso ...

at the cost of 549 lives. Three months later on August 15, U.S. and Canadian forces landed on Kiska expecting the same resistance like Attu; they later found the entire island empty, as most of the Japanese forces secretly evacuated weeks before the landing. In spite of enemy absence on the island, over 313 Allied casualties were sustained nonetheless through car accidents, booby trap

A booby trap is a device or setup that is intended to kill, harm or surprise a human or another animal. It is triggered by the presence or actions of the victim and sometimes has some form of bait designed to lure the victim towards it. The trap m ...

s, landmines, and friendly fire

In military terminology, friendly fire or fratricide is an attack by belligerent or neutral forces on friendly troops while attempting to attack enemy/hostile targets. Examples include misidentifying the target as hostile, cross-fire while en ...

, in which 28 Americans and four Canadians were killed in the exchange of fire between the two forces.

Submarine operations

Several ships were torpedoed within sight of West Coast West Coast or west coast may refer to:

Geography Australia

* Western Australia

*Regions of South Australia#Weather forecasting, West Coast of South Australia

* West Coast, Tasmania

**West Coast Range, mountain range in the region

Canada

* Britis ...

Californian cities such as Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world' ...

, Santa Barbara, San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the List of United States cities by population, eigh ...

, and Santa Monica

Santa Monica (; Spanish: ''Santa Mónica'') is a city in Los Angeles County, situated along Santa Monica Bay on California's South Coast. Santa Monica's 2020 U.S. Census population was 93,076. Santa Monica is a popular resort town, owing to ...

. During 1941 and 1942, more than 10 Japanese submarines operated in the West Coast and Baja California

Baja California (; 'Lower California'), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Baja California ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Baja California), is a state in Mexico. It is the northernmost and westernmost of the 32 federal entities of Mex ...

. They attacked American, Canadian, and Mexican ships, successfully sinking over 10 vessels including the Soviet Navy submarine ''L-16'' on October 11, 1942.

Bombardment of Ellwood

The United States continent was first shelled by the Axis on February 23, 1942, when the attacked the

The United States continent was first shelled by the Axis on February 23, 1942, when the attacked the Ellwood Oil Field

Ellwood Oil Field (also spelled "Elwood") and South Ellwood Offshore Oil Field are a pair of adjacent, partially active oil fields adjoining the city of Goleta, California, about west of Santa Barbara, largely in the Santa Barbara Channel. A r ...

west of Goleta

Goleta or La Goleta may refer to:

* ''Goleta'' (spider), a spider genus

* Goleta, California, United States, a suburban city in Santa Barbara County

* La Goleta, the Spanish and Portuguese name for La Goulette

La Goulette (, it, La Goletta), i ...

, near Santa Barbara, California

Santa Barbara ( es, Santa Bárbara, meaning "Saint Barbara") is a coastal city in Santa Barbara County, California, of which it is also the county seat. Situated on a south-facing section of coastline, the longest such section on the West Coas ...

. Although only a pumphouse and catwalk at one oil well were damaged, ''I-17'' Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

Nishino Kozo radioed Tokyo that he had left Santa Barbara in flames. No casualties were reported and the total cost of the damage was officially estimated at approximately $500–1,000.invasion scare

An invasion is a military offensive in which large numbers of combatants of one geopolitical entity aggressively enter territory owned by another such entity, generally with the objective of either: conquering; liberating or re-establishing con ...

along the West Coast.

Bombardment of Estevan Point Lighthouse

More than five Japanese submarines operated in Western Canada

Western Canada, also referred to as the Western provinces, Canadian West or the Western provinces of Canada, and commonly known within Canada as the West, is a Canadian region that includes the four western provinces just north of the Canada� ...

during 1941 and 1942. On June 20, 1942, the , under the command of Yokota Minoru,Estevan Point

Estevan Point is a lighthouse located on the headland of the same name on the Hesquiat Peninsula on the west coast of Vancouver Island, Canada.

During World War II, in 1942, the Estevan Point lighthouse was fired upon by the Japanese submarine ...

lighthouse on Vancouver Island

Vancouver Island is an island in the northeastern Pacific Ocean and part of the Canadian Provinces and territories of Canada, province of British Columbia. The island is in length, in width at its widest point, and in total area, while are o ...

in British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, ...

, but failed to hit its target. Though no casualties were reported, the subsequent decision to turn off the lights of outer stations caused difficulties for coastal shipping activity.

Bombardment of Fort Stevens

In what became the second attack on a continental American military installation during World War II, the , under the command of Tagami Akiji, surfaced near the mouth of the Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river rises in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia, C ...

in Oregon on the night of June 21 and June 22, 1942, and fired shells toward Fort Stevens. The only damage officially recorded was to a baseball field

A baseball field, also called a ball field or baseball diamond, is the field upon which the game of baseball is played. The term can also be used as a metonym for a baseball park. The term sandlot is sometimes used, although this usually refers ...

's backstop. Probably the most significant damage was a shell that damaged some large phone cables. The Fort Stevens gunners were refused permission to return fire for fear of revealing the guns' location and/or range limitations to the sub. American aircraft on training flights spotted the submarine, which was subsequently attacked by a U.S. bomber, but escaped.

Lookout Air Raids

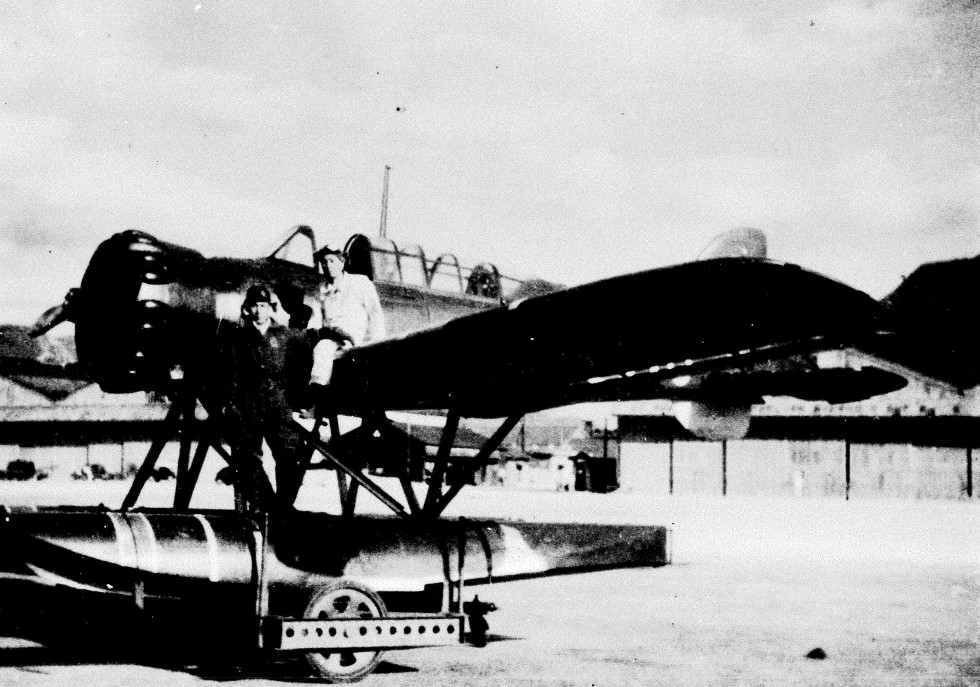

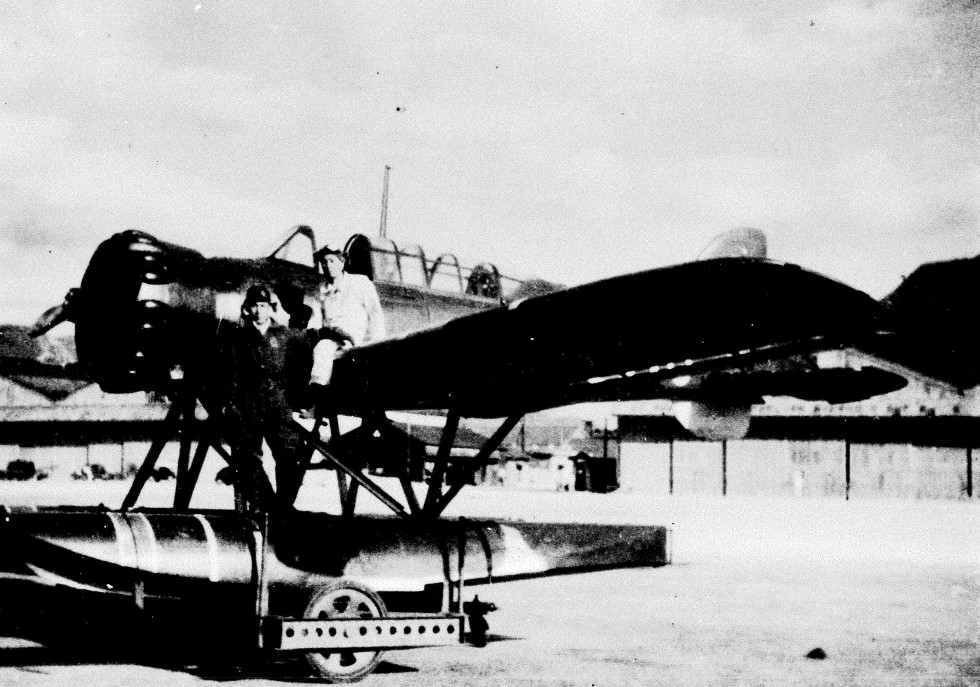

The Lookout Air Raids occurred on September 9, 1942. The second location to be subject to aerial bombing in the continental United States by a foreign power occurred when an attempt to start a forest fire was made by a Japanese Yokosuka E14Y1 "Glen"

The Lookout Air Raids occurred on September 9, 1942. The second location to be subject to aerial bombing in the continental United States by a foreign power occurred when an attempt to start a forest fire was made by a Japanese Yokosuka E14Y1 "Glen" seaplane

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft capable of takeoff, taking off and water landing, landing (alighting) on water.Gunston, "The Cambridge Aerospace Dictionary", 2009. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their tec ...

dropping two incendiary bomb

Incendiary weapons, incendiary devices, incendiary munitions, or incendiary bombs are weapons designed to start fires or destroy sensitive equipment using fire (and sometimes used as anti-personnel weaponry), that use materials such as napalm, t ...

s over Mount Emily

Mount Emily ( Tolowa: en-may ) is a mountain in the Klamath Mountains of southwestern Oregon in the United States. It is located in southern Curry County in the extreme southwest corner of the state, near Brookings, approximately from the Pacif ...

, near Brookings, Oregon

Brookings is a city in Curry County, Oregon, United States. It was named after John E. Brookings, president of the Brookings Lumber and Box Company, which founded the city in 1908. As of the 2020 census, the population was 6,744.

History

F ...

.

The seaplane, piloted by Nobuo Fujita

(1911 – 30 September 1997) was a Japanese naval aviator and warrant flying officer of the Imperial Japanese Navy who flew a floatplane from the long-range submarine aircraft carrier and conducted the Lookout Air Raids in southern Oreg ...

, had been launched from the Japanese submarine aircraft carrier

A submarine aircraft carrier is a submarine equipped with aircraft for observation or attack missions. These submarines saw their most extensive use during World War II, although their operational significance remained rather small. The most fam ...

''I-25''. No significant damage was officially reported following the attack, nor after a repeat attempt on September 29.

Fire balloon attacks

Between November 1944 and April 1945, the Japanese Navy launched over 9,000 fire balloons toward North America. Carried by the recently discovered Pacific

Between November 1944 and April 1945, the Japanese Navy launched over 9,000 fire balloons toward North America. Carried by the recently discovered Pacific jet stream

Jet streams are fast flowing, narrow, meandering thermal wind, air currents in the Atmosphere of Earth, atmospheres of some planets, including Earth. On Earth, the main jet streams are located near the altitude of the tropopause and are west ...

, they were to sail over the Pacific Ocean and land in North America, where the Japanese hoped they would start forest fires and cause other damage. About three hundred were reported as reaching North America, but little damage was caused.

Near Bly, Oregon

Bly is an unincorporated small town in Klamath County, Oregon, United States. By highway, it is about east of Klamath Falls. , the population was 207.

Geography

Bly is in southeastern Klamath County, slightly west of Lake County, along O ...

, six people (five children and a woman) became the only deaths due to an enemy balloon bomb attack in the United States when a balloon bomb exploded.Mitchell Recreation Area

Mitchell Recreation Area is a small picnic area located in the Fremont-Winema National Forests, Lake County, Oregon, near the unincorporated community of Bly. In it stands the Mitchell Monument, erected in 1950, which marks the only location in ...

in the Fremont-Winema National Forest.

A fire balloon is also considered to be a possible cause of the third fire in the Tillamook Burn

The Tillamook Burn was a series of forest fires in the Northern Oregon Coast Range of Oregon in the United States that destroyed a total area of of old growth timber in what is now known as the Tillamook State Forest. There were four wildfir ...

in Oregon. One member of the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion died while responding to a fire in the Umpqua National Forest

Umpqua National Forest, in southern Oregon's Cascade Range, covers an area of in Douglas, Lane, and Jackson counties, and borders Crater Lake National Park. The four ranger districts for the forest are the Cottage Grove, Diamond Lake, North Um ...

near Roseburg, Oregon

Roseburg is a city in the U.S. state of Oregon. It is in the Umpqua River, Umpqua River Valley in southern Oregon and is the county seat and most populous city of Douglas County, Oregon, Douglas County. Founded in 1851, the population was 23,683 a ...

, on August 6, 1945; other casualties of the 555th were two fractures and 20 other injuries.

Cancelled Axis operations

Germany

In 1940, the German Air Ministry

The Ministry of Aviation (german: Reichsluftfahrtministerium, abbreviated RLM) was a government department during the period of Nazi Germany (1933–45). It is also the original name of the Detlev-Rohwedder-Haus building on the Wilhelmstrasse ...

secretly requested designs from the major German aircraft companies for its ''Amerikabomber

The ''Amerikabomber'' () project was an initiative of the German Ministry of Aviation (''Reichsluftfahrtministerium'') to obtain a long-range strategic bomber for the ''Luftwaffe'' that would be capable of striking the United States (specifical ...

'' program, in which a long-range strategic bomber would strike the continental United States from the Azores

)

, motto =( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem= ( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

(more than away). Planning was complete in 1942 with the submittal of the program to Goering's RLM offices in March 1942, resulting in cogent piston-engined designs from Focke-Wulf

Focke-Wulf Flugzeugbau AG () was a German manufacturer of civil and military aircraft before and during World War II. Many of the company's successful fighter aircraft designs were slight modifications of the Focke-Wulf Fw 190. It is one of the ...

, Heinkel, Junkers and Messerschmitt

Messerschmitt AG () was a German share-ownership limited, aircraft manufacturing corporation named after its chief designer Willy Messerschmitt from mid-July 1938 onwards, and known primarily for its World War II fighter aircraft, in partic ...

(who had built the ultra-long-range Messerschmitt Me 261

The Messerschmitt Me 261 ''Adolfine'' was a long- range reconnaissance aircraft designed in the late 1930s. It looked like an enlarged version of the Messerschmitt Bf 110. It was not put into production; just three Me 261s were built and used pri ...

before WW II), but by mid-1944 the project had been abandoned as too expensive, with a serious increase in the need for defensive fighters, needing to come from Nazi Germany's by-then rapidly diminishing aviation production capacity.

Hitler had ordered that biological warfare should be studied only for the purpose of defending against it. The head of the Science Division of the Wehrmacht, Erich Schumann

Erich Schumann (5 January 1898 – 25 April 1985) was a German physicist who specialized in acoustics and explosives, and had a penchant for music. He was a general officer in the army and a professor at the University of Berlin and the Technic ...

, lobbied for Hitler to be persuaded otherwise: "America must be attacked simultaneously with various human and animal epidemic pathogens, as well as plant pests." The plans were never adopted because they were opposed by Hitler.

Italy

An Italian naval commander Junio Valerio Borghese

Junio Valerio Scipione Ghezzo Marcantonio Maria Borghese (6 June 1906 – 26 August 1974), nicknamed The Black Prince, was an Italian Navy commander during the regime of Benito Mussolini's National Fascist Party and a prominent hard-line Fascist ...

devised a plan to attack New York harbor with midget submarines

A midget submarine (also called a mini submarine) is any submarine under 150 tons, typically operated by a crew of one or two but sometimes up to six or nine, with little or no on-board living accommodation. They normally work with mother ships, ...

; however, as the tides of war changed against Italy, the plan was postponed and later scrapped.

Japan

Just after the attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii, j ...

, a force of seven Japanese submarines patrolled the United States West Coast. The Wolfpack made plans to bombard targets in California on Christmas Eve or Christmas Day of 1941. However, the attack was postponed to December 27 in order to avoid attacking during the Christian festival and offending German and Italian allies. Eventually the plan was canceled altogether for fears of American reprisal. In 1946, an unexploded Japanese torpedo was found near the Golden Gate Bridge

The Golden Gate Bridge is a suspension bridge spanning the Golden Gate, the strait connecting San Francisco Bay and the Pacific Ocean. The structure links the U.S. city of San Francisco, California—the northern tip of the San Francisco Pen ...

, and it has been interpreted as evidence of an attack, potentially targeting the bridge itself, in late December of 1941.

The Japanese constructed a plan early in the Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War, was the theater of World War II that was fought in Asia, the Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and Oceania. It was geographically the largest theater of the war, including the vast ...

to attack the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a conduit ...

, a vital water passage in Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Cos ...

, used during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

primarily for the Allied supply effort. The Japanese attack was never launched because Japan suffered crippling naval losses at the beginning of conflict with the United States and United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

(See: Aichi M6A

The is a submarine-launched attack floatplane designed for the Imperial Japanese Navy during World War II. It was intended to operate from I-400 class submarines whose original mission was to conduct aerial attacks against the United States.

...

).

The Imperial Japanese Army

The was the official ground-based armed force of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945. It was controlled by the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office and the Ministry of the Army, both of which were nominally subordinate to the Emperor o ...

launched Project Z (also called the Z Bombers Project) in 1942, similar to the Nazi German Amerika Bomber

The ''Amerikabomber'' () project was an initiative of the German Ministry of Aviation (''Reichsluftfahrtministerium'') to obtain a long-range strategic bomber for the '' Luftwaffe'' that would be capable of striking the United States (specifica ...

project, to design an intercontinental bomber capable of reaching North America. The Project Z plane was to have six engines of 5,000 horsepower each; the Nakajima Aircraft Company

The was a prominent Japanese aircraft manufacturer and aviation engine manufacturer throughout World War II. It continues as the car and aircraft manufacturer Subaru.

History

The Nakajima Aircraft company was Japan's first aircraft manufactur ...

quickly began developing engines for the plane, and proposed doubling HA-44 engines (the most powerful engine available in Japan) into a 36-cylinder engine. Designs were presented to the Imperial Japanese Army, including the Nakajima G10N

The Nakajima G10N ''Fugaku'' (Japanese: 富岳 or 富嶽, " Mount Fuji") was a planned Japanese ultra-long-range heavy bomber designed during World War II. It was conceived as a method for mounting aerial attacks from Japan against industrial ta ...

, Kawasaki Ki-91

The Kawasaki Ki-91 was a Japanese heavy bomber developed by Kawasaki Aircraft Industries during the later years of World War II.

Development

In early 1943, following the cancellation of the Nakajima Ki-68 and Kawanishi Ki-85 due to the failure ...

, and Nakajima G5N

The Nakajima G5N ''Shinzan'' (, "Deep Mountain") was a four-engined long-range heavy bomber designed and built for the Imperial Japanese Navy prior to World War II. The Navy designation was "Experimental 13-Shi Attack Bomber"; the Allied code name ...

. None developed beyond prototypes or wind tunnel models, save for the G5N. In 1945, the Z project and other heavy bomber projects were cancelled.

During the final months of World War II, Japan had planned to use bubonic plague

Bubonic plague is one of three types of plague caused by the plague bacterium (''Yersinia pestis''). One to seven days after exposure to the bacteria, flu-like symptoms develop. These symptoms include fever, headaches, and vomiting, as well a ...

as a biological weapon against U.S. civilians in San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the List of United States cities by population, eigh ...

, California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

, during Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night. The plan was set to launch at night on September 22, 1945. However, it was shelved because Japan surrendered on August 15, 1945.

Other alarms

False alarms

These false alarms have generally been attributed to military and civilian inexperience with war and poor radars of the era. Critics have theorized they were a deliberate attempt by the Army to frighten the public in order to stimulate interest in war preparations.[The Virtual Museum of The City of San Francisco The Army Air Forces in World War II; Defense of the Western Hemisphere]

/ref>

Alerts following Pearl Harbor

On December 8, 1941, "rumors of an enemy carrier off the coast led to the closing of schools in Oakland, California

Oakland is the largest city and the county seat of Alameda County, California, United States. A major West Coast of the United States, West Coast port, Oakland is the largest city in the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area, the third ...

," a blackout enforced by local wardens and radio silence followed that evening.[ The reports reaching Washington of an attack on San Francisco were regarded as credible.][ The affair was described as a test but Lt. Gen. ]John L. DeWitt

John Lesesne DeWitt (January 9, 1880 – June 20, 1962) was a 4-star general officer in the United States Army, best known for leading the Japanese American internment, internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II.

After the attack on Pe ...

of the Western Defense Command

Western Defense Command (WDC) was established on 17 March 1941 as the command formation of the United States Army responsible for coordinating the defense of the Pacific Coast region of the United States during World War II. A second major respo ...

said "Last night there were planes over this community. They were enemy planes! I mean Japanese planes! And they were tracked out to sea. You think it was a hoax? It is damned nonsense for sensible people to assume that the Army and Navy would practice such a hoax on San Francisco."[ Rumors continued on the West Coast in the following days. An alert of a similar nature occurred in the Northeast on December 9.][ "At noon advices were received that hostile planes were only two hours' distance away."][ Although there was no general hysteria, fighter aircraft from ]Mitchel Field

Mitchell may refer to:

People

*Mitchell (surname)

*Mitchell (given name)

Places Australia

* Mitchell, Australian Capital Territory, a light-industrial estate

* Mitchell, New South Wales, a suburb of Bathurst

* Mitchell, Northern Territor ...

on Long Island took the air to intercept the "raiders". Wall Street

Wall Street is an eight-block-long street in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. It runs between Broadway in the west to South Street and the East River in the east. The term "Wall Street" has become a metonym for t ...